leadership

How a Brilliant Gujarati Created ‘Sabki Pasand Nirma’ in His Backyard…!!!

Washing powder Nirma

Nirma!

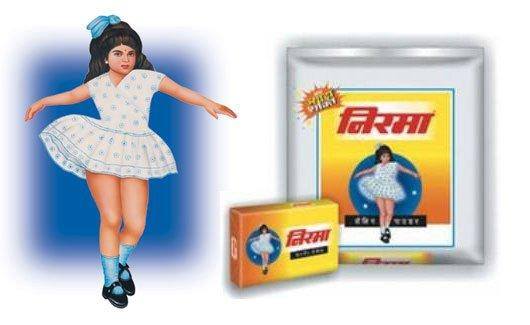

You may or may not use Nirma’s detergent powder to wash your clothes today, but it is highly unlikely that you would be unfamiliar with this jingle, or the advertisement featuring a young girl in a spotless white frock, twirling around playfully.

The catchy jingle and the young girl were exactly what Karsanbhai Patel, the founder of the Nirma brand, used to capture India’s attention to and overtake the big names in the market in the early 1980s.

This is Patel’s story of how he took a new detergent brand from his backyard to every middle-class house in India.

The year was 1969, and a brand named ‘Surf’ by Hindustan Lever Ltd (now Hindustan Unilever) had complete monopoly over the detergent market in India.

Priced between Rs 10 and Rs 15, it removed the stains from your clothes without harming your hands and was better for your clothes than a regular bar of washing soap.

However, the price was a major pain point for middle-class households, who found it to be beyond their budget. So, they continued to use soap bars.

Karsanbhai Patel, a chemist at the Gujarat Government’s Department of Mining and Geology, wanted to enter this very market and provide middle-class families like his, some relief.

He decided to make a detergent from scratch in his backyard in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, keeping in mind that that the price of the product, as well as the production costs, needed to be low.

He developed the formula, manufactured a yellow-coloured detergent powder, and started selling it for Rs 3. The brand was named Nirma, after Nirupama, Patel’s daughter, who had passed away in an accident.

He would go from door to door in each neighbourhood and give a ‘money back’ guarantee with every packet he sold.

A quality product, Nirma was also the lowest-priced branded washing powder at the time and became a huge hit in Ahmedabad.

Soon, Patel quit his job and decided to pursue this venture full time and take on the big players in the market. In those days, credit terms were the norm for retailers to follow. If Patel followed those, he would have been left with a huge cash crunch. Something he could not risk.

So, he devised a brilliant plan. One that would make Nirma a household name across India.

The washing powder was doing fairly well in Ahmedabad so Patel invested a little money in a television advertisement.

The catchy jingle—which stated that Nirma was “sab ki pasand”(everyone’s choice)—and the girl in a frilly white dress, became an instant hit.

Customers flocked to local markets to buy the product. However, the cunning Patel had withdrawn 90% of the stock, to lather up the demand.

For about a month, customers kept watching the advertisement, but when they would head out to purchase the washing powder, they would return home empty-handed.

The retailers pleaded with Patel to resume the supply, and after a month, he obliged and flooded the markets with the product.

The demand was sky high—so much so, in fact, that Nirma overtook Surf’s purchases by a large margin and became the most sold detergent that year. In fact, it managed to keep up its production and sales for a decade after this brilliant move.

While the product was affected by the obvious ups and downs of the market, Patel was not too concerned because he had decided to beyond manufacturing just a detergent. Soon, he launched toilet soaps, beauty soaps, shampoos and toothpaste.

Some products were successful, some not so much. But the brand Nirma never lost its firm hold on the market. Today, it has a 20% market share in soap cakes and about 35% in detergents.

In 1995, Patel established the Nirma Institute of Technology in Ahmedabad, and in 2003, he founded the Institute of Management and the Nirma University of Science and Technology in 2003.

He maintains that the passion for keeping up the business and expanding its branches across markets is rooted in love for his late daughter.

Patel has been presented with several prestigious awards, including the Padma Shri in 2010 and was also featured in the Forbes list of India’s wealthiest (2009 and 2017).

Undeterred by the lack of a management degree, unafraid to go up against big names, and equipped only with a sharp business sense and a brilliant mind, Karsanbhai is a legend in the entrepreneurial fraternity, today.

He has proved that it is not just his brand, but his brilliance which is “sab ki pasand” in India.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Source……..Tanvi Patel in http://www.the betterindia.com

Natarajan

How an Idea, …and an Ad … and Some Italians Got us the Auto Rickshaw!!!

After that glorious stroke at midnight in August 1947, following two centuries under the colonial yoke, India finally became free.

While citizens reeled under the after-effects of a hurried partition, leaders had a mammoth task at hand. They needed to plan and act towards the development of the new nation—economically and socially—and her people as producers and consumers.

“Correcting the disequilibrium” in the economy and an improvement in “the living standards” of the people featured in the objectives for the First Five Year Plan(1951-52 to 1955-56).

In a February 1947 session of then Bombay’s legislative assembly, a member raised the inhuman conditions of rickshaw pullers. This discussion set many wheels in motion.

Morarji Desai, then Home Minister of Bombay province, suggested that cycle ricks haws be discontinued.

haws be discontinued.

Navalmal Kundalmal Firodia, a freedom fighter, saw in this an opportunity to provide low-cost public transport to the country. The image of a three-wheeler “goods carrier” from a trade paper caught his eye and inspiration.

He submitted a plan to Desai and was told that if the vehicle was satisfactory from “a technical viewpoint”, it could be permitted under the public conveyance plan.

Firodia’s Jaya Hind Industries, set up a joint venture with Bachhraj Trading Corporation (later Bajaj Auto Private Limited), to replicate the vehicle in the image. It was manufactured by Italy’s Piaggio.

To better understand the nuances, Firodia bought a scooter and two three-wheeler goods carriers from the Italian company, studying the models and making several modifications to arrive at the final product.

Painted in hues of green and yellow, it was a mix of the hand-drawn carriages of the time and the automated two-wheeler. This contraption would soon become commonplace on Indian roads and affix its reliability on the Indian psyche.

The industrialist in Firodia had perhaps foreseen how it would enable independent Indians to undertake convenient and affordable trips around the country’s myriad cities and towns.

With the approval in the Bombay province, he saw and used another opportunity to popularise his vehicle—the prohibition of cycle rickshaws in Pune.

By December 1950, N Keshava Iyengar, the Mayor of Bangalore, approved the licenses of ten auto rickshaws in the capital of the princely state of Mysore. These vehicles “resembled a scooter pulling a passenger cabin attached to its rear”.

Iyengar inaugurated the first auto and is even said to have volunteered to take the vehicle’s owners, a Bangalorean man and h is Italian wife, on its maiden journey!

is Italian wife, on its maiden journey!

While people hailed the autos, the jatka union (hand-drawn cart) in Bangalore and the tongawallahs in Pune were unimpressed; the last-mile connectivity to and from public transport that auto rickshaws provided stood in their way.

As did the restrictions from the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1969.

A coffee-table about Kamalnayan Bajaj, the pioneer of Bajaj Auto, highlights this in the following words.

“In the beginning, we were licensed to make 1,000 scooters and auto rickshaws per month. In 1962, we applied to increase manufacturing capacity to 30,000 and 6,000 auto rickshaws per year. In 1963, we applied to increase capacity from 24,000 scooters to 48,000. In 1970, we asked for 100,000. Eventually, in 1971, the government approved an increase to 48,000.”

While the Bajajs and Firodias went their separate ways, with the auto rickshaw coming under the Bajaj Group, Bangalore’s ten auto rickshaws grew to 40.

The fact that middle-class Indians did not yet have enough disposable income to own vehicles furthered the popularity of the auto rickshaw, and it became the symbol of affordable urban transport.

This was true not only for India, but also for other developing countries. By 1973, Bajaj Auto was exporting three-wheelers to Nigeria, Bangladesh, Australia, Sudan, Bahrain, Hong Kong and Yemen.

In the financial year 1977, the company introduced rear engine auto rickshaws and sold 100,000 vehicles.

Until 1980, the vehicles were only allowed to carry two passengers at a time. However, this changed in the next two decades, and today, autos can transport as many as can fit themselves on the seats!

As per data from EMBARQ, auto rickshaws in tier-2 cities (population between 1 and 4 million) number between 15,000 and 30,000, to more than 50,000 in tier-1 cities (population more than 4 million).

The sector also employs an estimated 5 million people!

Additionally, the auto rickshaw union is one of the most organised labour groups in the country. They follow the latest trends—from unitedly aping a favourite actor’s haircut to expressing their thoughts on the vehicle.

While auto drivers have been criticised for irregularities in the fare system, and their disregard to the safety of passengers, autos remain the quintessential mode of intermediate or even end-to-end transport for an Indian.

Taxi aggregators born in India and abroad have take note of this, and as a result, co-opted the vehicle in their business models.

Interestingly, Firodia was not just responsible for bringing the three-wheeler goods chassis from Italy and converting it into a passenger vehicle in India, but also coined the term ‘auto-rickshaw’.

The word now finds a place in the Oxford Dictionary, and since its introduction in 1949, the auto has not gone off the road.

Featured image: Pxhere

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Source…..Shruti Singhal in http://www.the betterindia.com

Natarajan

தேநீர் கடையில் மனித நேயம் ….

செங்கல்பட்டு அரசு தலைமை மருத்துவமனைக்கு எதிராக இருக்கும் ஸ்ரீ கிருஷ்ணன் தேநீர் கடையில் எப்போதும் “ஜே ஜே’ என்று கூட்டம். இந்தக் கடையின் தேநீர், பலகாரங்கள் சுவையாக இருப்பது மட்டுமல்ல இந்தக் கூட்டத்திற்குக் காரணம். பினீஷும், அவரது அண்ணன் ஷிபுவும் சேர்ந்து இலவசமாக வழங்கி வரும் சுத்திகரிக்கப்பட்ட தண்ணீர்தான் கடையில் நிற்கும் கூட்டத்திற்கும், பலரது பாராட்டுகளுக்கும் காரணமாக அமைந்திருக்கிறது. வருஷத்தில் 365 நாட்களும் இந்த சுத்திகரித்த தண்ணீர் இலவசமாக இங்கு கிடைக்கும்.

தண்ணீர் எடுத்துக் கொள்ள வருபவர்கள் “தண்ணீர் வேண்டும்’ என்று யாரிடமும் கேட்கத் தேவையில்லை. கேனில் இருக்கும் தண்ணீரை எடுத்துக் கொள்ள வேண்டியதுதான். கேனில் தண்ணீர் தீர்ந்து விட்டால், தண்ணீர் இருக்கும் கேனைத் திறந்து தண்ணீர் எடுத்துக் கொள்ளலாம். தண்ணீர் பிடிக்க வருபவர்களுக்கு அத்தனை சுதந்திரம் வழங்கப்படுகிறது. இதற்காக, தண்ணீர் எடுப்பவர்கள் வடை, பஜ்ஜி அல்லது டீயை வாங்க வேண்டும் என்றோ நிர்பந்தமும் இல்லை. அதிசயம், ஆச்சரியமாக இருக்கும் இந்த தண்ணீர் பந்தலின் பின்னணியின் ரகசியம்தான் என்ன என்று தெரிந்து கொள்ள பினீஷை சமீபித்தோம்:

“”உண்மைதான்…. இங்கே யார் வேண்டுமானாலும் வந்து சுத்திகரிக்கப்பட்ட தண்ணீரை எவ்வளவு வேண்டுமானாலும் இலவசமாக எடுத்துக் கொள்ளலாம். கட்டுப்பாடுகள் இல்லை. ஒரு நாளைக்கு இருபது லிட்டர் தண்ணீர் கேன் நூறு முதல் நூற்றிப்பத்து வரை செலவாகிறது. இந்தத் தண்ணீர் கேன்களை இரண்டு ஏஜென்சிகளிடமிருந்து வாங்குகிறோம். ஒரு கேன் பத்தொன்பது ரூபாய். இப்ப குடிக்கிற தண்ணீர் மூலமாகத்தான் வியாதிகள் அதிகம் பரவுது. தவிர, குடி தண்ணீர் இலவசமா எங்கேயும் கிடைப்பதும் இல்லை. கொடுப்பதும் இல்லை. இங்கு வர்றவங்க எதிரே இருக்கிற மருத்துவமனைக்கு வரும் ஏழைபாழைகள்தான். அவங்களால விலை கொடுத்து தண்ணீர் வாங்க முடியாது. அவங்களுக்குப் பயன்படுகிற மாதிரி நாங்க எங்களை மாற்றிக் கொண்டோம். ஒரு வருஷமா இலவச தண்ணீர் வழங்கி வருகிறோம்.

எங்களுக்கு கேரளாதான் பூர்வீகம். இங்கே பிழைக்க வந்து இருபத்தேழு வருசமாச்சு. அப்பா ஆவடி டேங்க் பேக்டரியில் ஃபோர்மேனாக ஓய்வு பெற்றவர். நாங்க நான்கு சகோதரர்கள். ஒரு சகோதரர் செங்கல்பட்டு பேருந்து நிலையத்திற்குப் பக்கத்தில் கடை போட்டிருக்கிறார். ஒருவர் கேரளத்தில் வியாபாரம் செய்கிறார். நானும் அண்ணன் ஷிபுவும் இந்தக் கடையை நடத்தி வருகிறோம். பதினைந்து நாள் நான் கடையைப் பார்த்துக் கொள்வேன். அப்போது அண்ணன் ஷிபு குடும்பத்தைப் பார்க்க கேரளா போய்விடுவார். பதினைந்து நாட்கள் கழிந்து அவர் திரும்ப செங்கல்பட்டு வரும்போது நான் கேரளா புறப்பட்டுவிடுவேன்.

நான் எலெக்ட்ரானிக்சில் டிப்ளோமா படித்தவன். டீ கடை நடத்துவது குறித்து எந்த வருத்தமும் இல்லை. “என்ன வேலை செய்தாலும் உழைத்து வாழணும்.. தில்லுமுல்லு கூடாது என்று அப்பா எங்களை வளர்த்திருக்கிறார். அப்பா தேவையான சொத்தையும் சேர்த்து வைத்திருக்கிறார். காலை நான்கு மணிக்கு கடையைத் திறப்பேன். இரவு பத்து மணிக்கு வியாபாரத்தை நிறுத்திவிடுவேன். கடையில் நான்கு பேர் சம்பளத்திற்கு வேலை செய்கிறார்கள். எல்லாரும் உள்ளூர்க் காரர்கள்.

இந்தத் தண்ணீர் சேவைக்கு முக்கிய காரணம், எனது கடையிருக்கும் கட்டடத்தின் உரிமையாளர் சேகர்தான். தங்கமான மனதுக்காரர். எங்களை காலி செய்யுமாறு பலரும் அவரிடம் பேசினார்கள். அழுத்தம் கொடுத்தார்கள். ஆனால் அவர் எங்களைக் காலி செய்யச் சொல்லவில்லை. அதுமட்டுமல்ல, பல ஆண்டுகளாக வாடகையையும் அவர் உயர்த்தவில்லை. அவர் எங்களுக்கு இப்படி உதவும் போது, நாமும் பிறருக்கு உதவலாமே என்ற எண்ணத்தில் எங்களுக்கு தோன்றியதுதான் இந்த இலவச தண்ணீர் வசதி.

வீட்டுக்கு வரும் விருந்தாளிகளுக்கு வந்தவுடன் பிரியாணியோ.. சாப்பாடோ தருவதில்லை. குடிக்க கொஞ்சம் தண்ணீர் கொடுப்போம். தாகம் வரும் போதுதான் குடி தண்ணீரின் அருமை தெரியும் என்பதில்லை. காசு கொடுத்து தண்ணீர் வாங்கும் போதும் தண்ணீரின் அருமை புரியும். அதுவும் கையில் காசு இல்லாதவர்கள் தண்ணீர் வாங்க படும் அவதியிருக்கிறதே.. அதை விவரிக்க முடியாது. ஒரு நாளைக்கு இரண்டாயிரம் ரூபாய் தண்ணீருக்காகச் செலவாகிறது உண்மைதான். மருத்துவமனைக்கு வரும் பெரும்பாலானவர்கள் எங்கள் கடைக்குத்தான் வருவார்கள். அவர்களால்தான் நாங்கள் பிழைக்கிறோம். அதற்கு கைமாறாக இந்த சிறிய பங்களிப்பை நானும் அண்ணனும் செய்யத் தொடங்கியிருக்கிறோம். எங்களது நோக்கத்தைத் தெரிந்து கொண்டதினால், அரசியல் கட்சிக்காரர்கள் கடை அடைப்பு நடத்தினாலும் எங்கள் கடையைத் திறந்து கொள்ள அனுமதிப்பார்கள்.

மருத்துவமனைக்கு வரும் சாதாரணமானவர்களுக்கு “குடிக்க தண்ணீர் கிடைக்க வேண்டும் ..தண்ணீர் கிடைக்கா விட்டால் அவர்கள் அவதிப்படுவார்கள் என்ற ஒரே காரணத்திற்காக எங்களுக்கு அனுமதி தரப்படுகிறது’ என்கிறார் பினீஷ்.

Source….. பிஸ்மி பரிணாமன் in http://www.dinamani.com dated 13/10/2018

Natarajan