environment

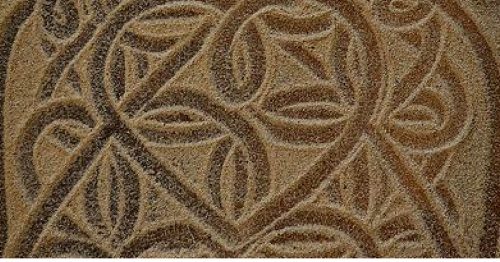

Hiding in plain sight; Rangoli, Kolam designs and what they mean…

Every day, my mother religiously performed a ritual. Rain or shine, she never skipped this ritual even for a day. Every day, she drew enchanting kolam patterns using rice flour.

On special occasions, the white kolam designs were made with wet rice flour paste accompanied by thick strips of earth colored borders made with red sand mixed with water.

My mother is proud of her kolam design skills. She is not alone. It seems no self-respecting South Indian woman will tolerate anyone questioning her ability to conjure up kolam designs at will.

Millions of women from different communities in South India practice this art form every day.

For over 38 years, I considered Kolam to be just another ritual among the long list of rituals Indian women seem to follow. However, when I decided to dig deeper to understand the significance of kolam designs, I was surprised at what I discovered.

The threshold is a key concept in Tamilian culture. Even historical Tamil literature such as the Sangam literature (Tamil literature in the period spanning 300BC to 300 CE) is divided into the akam (inner field) and the puram (outer field).

That’s not all.

In one of Nammalvar’s (the fifth among the 12 Alwar saints who espoused Vaishnavism) hymns, the God in the poem is the God of the threshold. Of course, every newly married bride formally becomes a part of the household when she steps overs the threshold.

Should we then conclude that kolam designs are a celebration of the threshold?

Different interpretations of the significance of kolam designs

Here are a few explanations I came across in my quest to unearth the real significance of the kolam ritual.

The most common understanding has been that the idea of using rice flour is to provide food to ants, insects and small birds.

If that is the case, what’s stopping men from participating in this noble deed?

While I did not find an answer, a common sense reasoning is that women have traditionally carried the burden of maintaining the home and the kolam ritual automatically became a part of the woman’s domain.

That’s also a reason why my mother and my aunts believe that women see it as a key ritual that helps them improve their concentration and patience, two key components needed to run a household!

Here is another interpretation recorded in Lance Nelson’s study of Kolam.

“Bhumi Devi [earth goddess] is our mother. She is everyone’s source of existence. Nothing would exist without her. The entire world depends on her for sustenance and life. So, we draw the kolam first to remind ourselves of her. All day we walk on Bhumi Devi. All night we sleep on her. We spit on her. We poke her. We burden her. We do everything on her. We expect her to bear us and all the activities we do on her with endless patience. That is why we do the kolam.”

According to Devdutt Pattnaik, author and mythologist –

“A downward pointing triangle represented woman; an upward pointing triangle represented man. A circle represented nature while a square represented culture. A lotus represented the womb. A pentagram represented Venus and the five elements.”

Kolams connects the dots in more than one way.

Cultural practices are common across the length and breadth of India. They also transcend regions.

The concept of Kolam is definitely not unique to Tamil speaking community in India. For example, in the Telugu language, it is called ‘Muggulu’, and it’s known as ‘Rangoli’ in the Kannada language.

But the idea of drawing patterns on the ground transcends India and can be found in other cultures as well!

Anil Menon, a computer scientist, and a speculative novelist has compiled findings from his research on similar practices among cultures separated by oceans. Here are some tidbits from Menon’s work.

British anthropologist, John Layard, found that the patterns drawn on the sand by the tribal population of Malekula (an island that’s a part of The Republic of Vanuatu, situated 1000 miles east of Australia) are similar to the kolam patterns popular in Tamil Nadu!

Here is the proof.

There is also a possibility that kolam designs were an early form of pictorial language!

Dr Gift Siromani, through his path-breaking work, has proved that it is possible to create any kolam pattern using a combination of strokes.

Rituals and cultural practices are to be cherished

I did not think much of the kolam designs my mom drew every day. But a sudden spark of curiosity led me to unexpected findings and the joy of discovering human beings are connected to each other in more ways than we can imagine.

Physical boundaries, cultural differences, and racial definitions are just imaginary barriers we have erected over a period of time. Our lives are always connected just like the dots of the kolam my mom draws.

SOURCE….Srinivas Krishnaswamy in http://www.the betterindia.com

Natarajan

இவருக்கு கை கிடையாது… அவருக்கு கண் தெரியாது… இணைந்து ஒரு காடே வளர்த்திருக்கிறார்கள்!

“உங்களால் பறக்க முடியாவிட்டால் ஓடுங்கள்; ஓடமுடியாவிட்டால் நடந்துசெல்லுங்கள்; நடக்கவும் முடியாவிட்டால் தவழ்ந்து செல்லுங்கள். ஆனால், எதைச் செய்தாலும் உங்கள் இலக்கை நோக்கி முன்னேறிக் கொண்டே இருங்கள்”- மிகவும் பிரபலமான வரிகள் இவை. தன்னம்பிகையை தட்டிக்கொடுத்து வளர்க்கும் இந்த வரிகளுக்கு வாழும் சாட்சிகளாக இரண்டு பேர் சீனாவில் இருக்கிறார்கள். பார்வை இல்லாத ஒருவரும், இரு கைகளை இழந்த ஒருவரும் சேர்ந்து பத்தாயிரம் மரங்களை வளர்த்திருக்கிறார்கள்.

புற்கள், மரங்கள் என பச்சைப் பசுமையாய் இருந்த வடகிழக்கு சீனாவின் ஏலி என்கிற கிராமத்துக்கு குவாரி ஒன்று செயல்பட ஆரம்பித்திருக்கிறது. குவாரியின் வருகைக்குப் பின் சுற்றி இருக்கிற இடங்கள் எல்லாம் மாசுப்படுகின்றன. ஆற்றில் கழிவுகள் கலக்கின்றன. அதனால் ஆற்றில் இருக்கிற மீன்கள் இறக்கின்றன. அதேபகுதியில் ஜியா ஹைக்சியா என்பவர் வசித்து வருகிறார். 2000-வது வருடத்தில் குவாரியில் நடைபெற்ற ஒரு வெடி விபத்தில் ஜியா ஹைக்சியா சிக்கிக்கொள்கிறார். விபத்தின் விளைவால் தனது கண் பார்வையை நிரந்தரமாக இழக்கிறார். திடீரென பார்வை இழந்ததும், விபத்துக்கு முன்னர்தான் பார்த்த இடங்களை, மனிதர்களை, நினைத்து நினைத்து உடைந்து போகிறார். பிறவியில் பார்வை இல்லாமல் இருந்திருந்தால் வாழப் பழகி இருக்கும் என நினைக்கிற வெங்க்யூ ஒரு கட்டத்தில் தற்கொலைக்கு முயல்கிறார்.

அதே கிராமத்தில் ஜியா வேங்க்யூ என்கிற நபர் வசித்து வருகிறார். அவர் 3 வயதாக இருக்கும்போது மின்சாரம் தாக்கிய விபத்தில் தனது இரு கைகளையும் இழக்கிறார். கைகளை இழந்தவர் துவண்டுபோகாமல் தனது கால்களைப் பயன்படுத்தி எல்லா வேலைகளையும் செய்துவருகிறார். கிராமத்தில் இருக்கிற ஊனமுற்ற பாடல் குழுவில் இணைந்து, பாடல்கள் பாடுவதை தொழிலாகக் கொள்கிறார். ஜியா வேங்க்யூவின் பால்ய காலங்களில் ஜியா ஹைக்சியாவுடன் பயணித்தவர். சிறு வயதில் இருந்தே இருவரும் நண்பர்களாக இருக்கிறார்கள். இருவரது வீடுகளும் அருகருகே இருக்கிறது.

பார்வை இழந்து, மன உளைச்சலில் இருக்கும் ஜியா ஹைக்சியாவை கைகளை இழந்த ஜியா வேங்க்யூ சந்திக்கிறார். “எனக்கு நீ கையாக இரு. உனக்கு நான் கண்ணாக இருக்கிறேன்” என சொல்கிறார். கிடைத்த ஆறுதல் ஒரு பிடிப்பாக தெரியவே, ஜியா ஹைக்சியா அவரோடு இணைகிறார். ஒருவருக்கு ஒருவர் துணை என நடக்க ஆரம்பிக்கிறார்கள். ஆறுகளைத் தாண்டும் போதெல்லாம் ஹைக்சியாவை தூக்கிக் கொண்டு நடக்கிறார் ஜியா வேங்க்யூ. எங்கு சென்றாலும் இருவரும் இணைந்தே செல்கிறார்கள். வறண்டு போய் கிடக்கிற கிராமத்துக்கு நம்மால் முடிந்த ஒன்றைச் செய்ய வேண்டும் என இருவரும் பேசிக்கொள்கிறார்கள். அவர்கள் மாற்றுத்திறனாளிகள் என்பதைக் கடந்து யோசிக்க ஆரம்பிக்கிறார்கள். இருவரும் தங்களைச் சுற்றி இருக்கிற சூழல் மாசுபட்டுக் கிடப்பதை உணர்கிறார்கள்.. குவாரியில் இருந்து வருகிற கழிவுகள் ஆற்றில் கலந்தும், காற்றில் கலந்தும் இருப்பதை அறிந்து கிராமத்தில் மரம் வளர்ப்பது என முடிவெடுக்கிறார்கள்.

கிராமத்தைச் சுற்றி 800 மரக்கன்றுகளை நடவு செய்கிறார்கள். கைகளை இழந்த ஜியா வேங்க்யூ கழுத்துக்கு தோளுக்கும் இடையில் கம்பு போன்ற ஒன்றை பயன்படுத்தி தண்ணீர் எடுப்பது, மண் அள்ளுவது என பல வேலைகளைச் செய்கிறார். மரம் நடுவதற்கான குழிகளை தோண்டும் அவர்களின் முயற்சியை ஊர் மக்கள் கேலி செய்கிறார்கள். “கை இல்லாதவனும் கண்ணு தெரியாதவனும் சேர்ந்து என்ன பண்ணப் போறாங்களோ” என கேலியும் கிண்டலும் அதிகரிக்கிறது. ஆனால், அவர்கள் இருவரும் மரங்கள் வளரும் எனக் காத்திருக்கிறார்கள். மரக்கன்றுகள் வேர்பிடித்திருக்கும் என நினைத்தவர்களுக்கு ஏமாற்றமே கிடைத்திருக்கிறது. 800 மரங்களில் 2 மட்டுமே உயிர்ப்பிடித்திருக்கிறது. மற்ற அனைத்தும் இருக்கிற தடம் இல்லாமல் அழிந்து போயிருக்கிறது. மரம் நடுவதும் வளர்ப்பதும் எளிதானது என நம்பியவர்கள் அது சாதாரண காரியம் இல்லை என உணர்கிறார்கள்.

தோல்வியில் சோர்ந்து போயிருந்த ஜியா ஹைக்சியாவுடன் மனம் விட்டுப் பேச ஆரம்பிக்கிறார் ஜியா வேங்க்யூ. “விடாம முயற்சி பண்ணுவோம். நிச்சயம் நமக்கு ஒரு நாள் விடை கிடைக்கும்” என தன்னம்பிக்கையை விதைக்கிறார் வேங்க்யூ. பிறகு மரக்கன்றுகள் இறந்து போனதற்கு காரணம் தண்ணீர் இல்லாமல், நிலம் காய்ந்து போய் இருப்பதுதான் என்பதைக் கண்டறிகிறார்கள். தண்ணீர் போகிற பாதையில் மரக்கன்றுகளை நடுவதுதான் சிறந்த வழி என முடிவு செய்கிறார்கள்.

பின், மரக்கன்றுகள் வாங்குவதற்கான பணம் இல்லாமல் இருக்கிறார்கள். மரங்களில் இருந்து வெட்டி எடுக்கப்படுகின்ற கிளைகளை நடவு செய்கிற முறையைப் பற்றி கேள்விப்படுகிறவர்கள், ஊரில் இருக்கிற மரத்தில் இருந்து கிளைகளை வெட்ட முடிவு செய்கிறார்கள். ஜியா ஹைக்சியாவின் உதவியுடன் ஜியா வேங்க்யூ மரம் ஏறி கிளைகளை வெட்டுகிறார். வெட்டிய கிளைகளை ஆறுகளின் ஓரத்தில் நடவு செய்கிறார்கள். தினமும் அம்மரக்கன்றுகளை கண்காணித்து வருகிறார்கள். ஆறு மாதங்கள் எந்த மாற்றமும் இல்லாதிருந்த அக்கன்றுகள் துளிர்க்க ஆரம்பிக்கின்றன. தனிமரம் தோப்பாவதை காண்கிற மக்கள் அவர்களுக்கு உதவி செய்ய ஆரம்பிக்கிறார்கள். இருவரது கனவுகளும் சேர்ந்து ஒரு நாள் மரங்களாகின்றன. அப்படி அவர்கள் நட்ட கன்றுகள் எண்ணிக்கை இப்போது பத்தாயிரத்தைத் தாண்டி நிற்கிறது. அவை அனைத்தும் இன்று மரங்களாக வளர்ந்து நிற்கின்றன.”அடுத்தத் தலைமுறைக்கு கொடுத்து போக எங்களிடத்தில் மரங்கள் இருக்கின்றன” எனச் சொல்லும் இரு நண்பர்களும் “எங்களின் இறுதி மூச்சு இருக்கிற வரை மரம் நடுவோம். எங்களைப் போல ஒவ்வொரு தனி மனிதரும் ஒரு மரம் வளர்த்தால் இயற்கையை எளிதாக காப்பாற்றி விடலாம்” என்கிறார்கள்.

ருக்கிறவர்கள் இல்லாதவர்களுக்கு கொடுப்பதில் இருக்கிற ஆனந்தத்தை விட, இல்லாதவர்கள் இருப்பவர்களுக்கு கொடுத்துவிட்டு போவதில் தான் அதிகம் இருக்கிறது. ”மரம் நடுங்கள் என்றெல்லாம் சொல்லவில்லை; எழுந்து நடங்கள்” எனச் சொல்கின்றன இவர்களின் செயல்பாடுகள்.

இவர் அவரின் கை. அவர் இவரின் கண். எங்கேயே ஒலிக்கிறது ஒரு பாடல்

“ஒண்ணுக்கொண்ணு தான் இணைஞ்சு இருக்கு…

Source…

ஜார்ஜ் அந்தோணி in

A Newspaper Mistake that afforded Alfred Nobel to Read his own “obituary ” …!

THE NEWSPAPER ERROR THAT SPARKED THE NOBEL PRIZE

“The merchant of death is dead,” blasted a French newspaper in April 1888, bidding good riddance to Swedish inventor and arms manufacturer Alfred Nobel, who “became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before.” Pretty harsh words for an obituary, especially when its subject was still very much alive. But even if the rumors of his demise were greatly exaggerated, the inventor of dynamite was not about to let the details of his legacy be similarly blown out of proportion, and so Nobel set out to ensure that his name would forever be tied to humankind’s highest achievements, and not its destructive potential.

“Nobel was a torrent of ideas, a perpetual inventor,” writes Jay Nordlinger in Peace, They Say: A History of the Nobel Peace Prize. It was no accident. His father was an engineer and inventor who specialized in blowing things up, and whose undersea naval mines had been used by the Russians to keep the vaunted British navy from besieging St. Petersburg during the Crimean War of the 1850s. Born in 1833 in Stockholm, young Alfred never earned a degree or attended college, but in addition to absorbing his father’s explosive knowledge, he traveled widely, learned several languages and trained under a world-renowned chemist in Paris. At the age of 24 he obtained his first patent, the first of more than 350 he would earn in his lifetime.

Nobel’s biggest breakthroughs came when he successfully harnessed the destructive power of nitroglycerin, including in dynamite, his most famous invention, which facilitated canals, tunnels and other infrastructure projects. Nobel was also, says Nordlinger, a “genius businessman” and entrepreneur, who not only invented the products he sold but also directed their manufacturing and marketing. And he was a prolific writer and lifelong bachelor. “My only wish is to devote myself to my profession, to science,” he wrote in 1884. “I look upon all women — young and old — as disturbing invaders who steal my time.”

But the Swede’s single-minded devotion to his work paid off. He would eventually oversee more than 90 labs and factories operating in more than 20 countries around the world, and he spent most of his time traveling between them, prompting French writer Victor Hugo to label him “Europe’s wealthiest vagabond.” Nobel’s employees adored their vagabond chief, though, and his factories offered free medicine and medical care. In addition to his generosity, Nobel was known for his insatiability, once observing, “I have two advantages over competitors: Both moneymaking and praise leave me utterly unmoved.”

What moved him profoundly, however, was being pronounced dead and a merchant of death. The press had confused Alfred’s passing with that of his older brother Ludvig, who succumbed to tuberculosis in 1888. It was a regrettable mistake that nonetheless afforded Nobel the rare opportunity to read his own obituary. “It pained him so much he never forgot it,” says Kenne Fant in Alfred Nobel: A Biography, and the insatiable inventor “became so obsessed with his posthumous reputation” that he would not rest until he had crafted “a cause upon which no future obituary writer would be able to cast aspersions.”

Finally, on Nov. 27, 1895, the inspired inventor sat down at a desk in the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris and, in handwritten Swedish with no help from a lawyer, penned a four-page document that would become one of history’s most notable last will and testaments. In it, he left 31 million Swedish kroner (equivalent to about $250 million today), the bulk of his estate, to be invested and the interest from which given “in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.” Four random gentlemen at the club were asked to witness the document, which now resides in a vault at the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, and the rest is history.

When he died, for real, the following year, Nobel’s will shocked his disappointed relatives, as well as the Swedish royal family, upset that he would establish a valuable prize whose competition was open to everyone, not just Swedes. But the prolific inventor, resolute and innovative to the end, had gone out with a bang, and true to his wishes, the name Alfred Nobel, no longer linked to death and destruction, would forever be associated with progress, peace and the very best in human achievements.

Source…Input from a friend of mine

Natarajan

வாரம் ஒரு கவிதை…” ஒரு புள்ளியில் தொடங்கிய பயணம் “