Source….Prannay Kumar and Chetan Anand in http://www.the hindu.com

Natarajan

More often than not, industrial infrastructures are an eyesore, especially when they are smack in the middle of a beautiful city like Toronto. So for the past hundred years, Canada’s second-largest municipal electricity distribution company, Toronto Hydro, has been disguising substations into quiet little houses that blend right in with the neighbourhood. Some appear like grand Georgian mansions or late-Victorian buildings, while others look like humble suburban homes. Even the most sharp-eyed resident couldn’t tell these faux homes apart. Some are not even aware they are living next door to a transformer.

This is not a house. Photo credit: City of Toronto Archives

Toronto was first electrified in the late 1880s. At that time a number of small private companies were supplying electrical demands. Then in 1908, Torontonians voted overwhelmingly for the formation of a municipal electricity company, and Toronto Hydro came into being in 1911.

From the very beginning, Toronto Hydro was keen not to have ugly conglomerations of metals, switches and wires robbing the city’s urban and suburban neighbourhood of its beauty. So each substation they built was wrapped around by a shell of masonry and woodwork carefully designed to resemble residential homes. A driveway and some low-maintenance shrubs in the garden helped complete the deception.

The earliest known substation, dating from 1910 and located at 29 Nelson St. in the John and Richmond area, looks like a four-storey Victorian-era warehouse or perhaps an office building with a grand entrance and raised horizontal brick banding. One of the grandest of these structures is the Glengrove Substation, built in 1931. This Gothic building with its large oak doors, leaded glass windows and long narrow windows reminiscent of Medieval times, it’s no wonder that Toronto Hydro employees call it the “Flagship” or the “Castle”.

As architectural styles evolved, so did the camouflage. From grandiose buildings of the pre-depression era to ranch style houses that became popular with the booming post-war middle class of the 1940s to 1970s, to progressively more modernist structures with flat roof and smooth white exterior. These substation homes were so authentic that they were sometimes broken into by burglars.

There used to be over 270 substation homes scattered across Toronto. According to Spacing Toronto, as of 2015, 79 of these substations are still active.

Source….Kaushik in http://www.amusingplanet.com

Natarajan

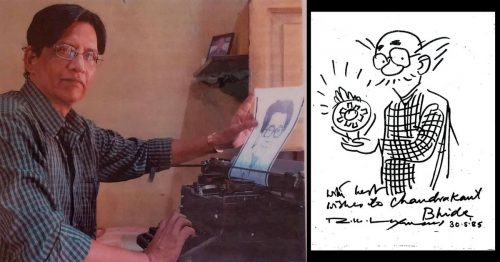

A typist is required to be fast and accurate, and while he proved to be precisely that, Bhide was much more too. Throw in artistic to those set of skills, and you have Chandrakant Bhide.

“Sachin Tendulkar’s curls gave me the most trouble!”

Chandrakant Bhide is a typist by profession. In 1967 he joined the Union Bank of India and worked there for 3 decades.

A rather implausible scenario for Tendulkar’s curls to give him grief, right?

A typist is required to be fast and accurate, and Bhinde proved he was precisely that but more too.

Throw in artistic to those set of skills, and you have Chandrakant Bhide.

“Art helped me meet important people. How else does a modest typist like me get to meet and be appreciated by people like R. K. Laxman and Mario Miranda,” questions Mr Chandrakant Bhide?

Mr Bhide is anything but ‘just a typist’. His art is indicative of his sheer talent and why the likes of the above-mentioned greats were his fans.

Growing up, he always wanted to join an art school – specifically the Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai.

But financial constraints forced him to take a more secure job.

“One day I was asked to type out a list of phone numbers, instead of typing a regular list, I made one in the shape of a telephone instrument,” he remembers. That was the beginning of many more artistic endeavours to come.

“I typed out Lord Ganesha using the ‘x’ key and it was published in the Maharashtra Times newspaper in 1975. I slowly started improvising and started using other keys like ‘_’, ‘=’, ‘@’, ‘-’, ‘,’ in my sketches,” recalls Bhide.

His father’s words inspired him to be better and do better. Each sketch takes him about 5-6 hours to complete.

“I hold the paper with my left hand and use the fingers on my right hand to type out the symbols. The different shades in a sketch are added by using a light or a hard touch on the keys. My hands start aching after 10-15 minutes, and so I need constant breaks,” he adds.

One day, Mr Bhide sketched RK Laxman’s, Common Man. It was a time when Xerox machines had just made their appearance. His friend helped him get copies and requested to keep the original.

“I wanted to show the sketch to R.K. Laxman sir. I went to his office without an appointment and showed it to the cartoonist. Laxman sir was so thrilled with it that he said the result could not have been better with a pen and brush. We spent 1.30 hours talking, and I even mentioned my lost dream of studying in Sir J.J. School of Art, and he said, you can be an artist anyway!” he recalls.

Bhide continued to keep in touch with the famed cartoonist and takes great pride in having several original ‘Common Man’ sketches.

Over the years, Mr Bhide has created almost 150 sketches including several of people he admires including Amitabh Bachchan, Dilip Kumar, Sunil Gavaskar, Dr Ambedkar, Lata Mangeshkar and more.

But it was Sachin Tendulkar’s curls that frustrated the master typer! “I finally used the ‘@’ symbol to get it right,” he recalls.

One of his fondest memories was meeting up with renowned cartoonist and illustrator Mario De Miranda via a common friend, the famous Behram Contractor also known as the Busy Bee. “I was nervous when I rang the bell to Mario’s home, but he soon put me to ease. Once he saw some of my sketches based on his famous characters (Ms Fonseca, Godbole and Boss), he autographed one of my sketches with the words – ‘I wish I could draw like you type.’ That was my biggest compliment,” says Mr Bhide.

Mario De Miranda encouraged and inaugurated Mr Bhide’s first exhibition. He went on to hold several more, including ones in festivals like IIT Mumbai’s Mood Indigo and IIT-Kanpur’s Antaragini.

Mr Chandrakant Bhide retired from the Union Bank of India in 1996. He approached the administration department with a request to buy his beloved companion, his typewriter but was denied it as it was against policy. But on the day of his farewell, the chairman of the Bank allowed him to buy it for just Rs. 1.

Today, the typewriter still holds a place of pride in his household. “It has been with me for fifty years now, I understand it, it understands me,” he chuckles.

Source….Uma Iyer in http://www.the betterindia.com

Natarajan

There is something beautifully Indian about the fragrance of sandalwood. Sweet, warm, rich and woody, it is a scent that is deeply interwoven with the nation’s history and heritage. This is, perhaps, one of the many reasons why the Mysore Sandal Soap has held a special place in the hearts of Indians for more than a century.

One hundred and one years ago, in May 1916, Krishna Raja Wodiyar IV (the then Maharaja of Mysore) and Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya (the then Diwan of Mysore), set up the Government Sandalwood Oil factory at Mysore for sandalwood oil extraction.

The primary goal of the project was to utilise the excess stocks of the fragrant wood that had piled up after World War I halted the export of sandalwood from the kingdom of Mysore (the largest producer of sandalwood in the world at the time).

Two years later, the Maharaja was gifted a rare set of sandalwood oil soaps. This gave him the idea of producing similar soaps for the masses which he immediately shared with his bright Diwan. In total agreement about the need for industrial development in the state, the enterprising duo (who would go on to plan many projects whose benefits are still being reaped) immediately got to work.

A stickler for perfection, Visveswaraya wanted to produce a good quality soap that would also be affordable for the public. He invited technical experts from Bombay (now Mumbai) and made arrangements for soap making experiments on the premises of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). Interestingly, the IISc had been set up in 1911 due to the efforts of another legendary Diwan of Mysore, K Sheshadri Iyer!

From the talent involved in the research happening at IISc, he identified a bright, young industrial chemist called Sosale Garalapuri Shastry and sent him to England to fine tune his knowledge about making soap. Affectionately remembered by many as Soap Shastry, the hardworking scientist would go on to play a key role in making Visveswaraya’s dream a reality.

After acquiring the required knowledge, Shastry quickly returned to Mysore where the Maharaja and his Diwan were waiting anxiously. He standardized the procedure of incorporating pure sandalwood oil in soaps after which the government soap factory was established near K R Circle in Bengaluru.

The same year, another oil extraction factory was set up at Mysore to ensure a steady supply of sandalwood oil to the soap making unit. In 1944, another unit was established in Shivamoga. Once the soap hit the market, it quickly became popular with the public, not just within the princely state but across the country.

However, Shastry was not done yet. He also created a perfume from distilled sandalwood oil. Next, he decided to give the Mysore Sandal Soap a unique shape and innovative packaging. In those days, soaps would normally be rectangular in shape and packed in thin, glossy and brightly coloured paper. To help it stand out from the rest, he gave the soap an oval shape before working on a culturally significant packaging.

Cognizant of the Indian love of jewels, Shastry designed a rectangular box resembling a jewellery case— with floral prints and carefully chosen colours. At the centre of the design was the unusual logo he chose for the company, Sharaba (a mythical creature from local folklore with the head of an elephant and the body of a lion. A symbol of courage as well as wisdom, the scientist wanted it to symbolise the state’s rich heritage.

The message ‘Srigandhada Tavarininda’ (that translates to ‘from the maternal home of sandalwood’) was printed on every Mysore Sandal Soapbox. The aromatic soap itself was wrapped in delicate white paper, similar to the ones used by jewellery shops to pack jewels.

This was followed by a systematic and well-planned advertising campaign with cities across the country carrying vibrant signboards in neon colours. Pictures of the soapbox were noticeable everywhere, from tram tickets to matchboxes. Even a camel procession was held to advertise the soap in Karachi!

The out-of-the-box campaign led to rich results. The soap’s demand in India and abroad touched new heights, with even royal families of foreign nations ordering it for themselves. Another important turning point for the company was when, in 1980, it was merged with the oil extraction units (in Mysuru and Shivamoga) and incorporated into one company called Karnataka Soaps and Detergent Limited (KSDL).

However, in the early 1990s, the state-run firm did face a rough patch due to multinational competition, declining demand and lack of coordination between sales and production departments. As losses started rising, it was given a rehabilitation package by BIFR (Board for Industrial & Financial Reconstruction) and KSDL grabbed the lifeline with both hands.

The company streamlined its way of functioning and soon it had started showing profits again. Thanks to rising profits year after year, it had soon wiped out all its losses and repaid its entire debt to BIFR by 2003. The company also successfully diversified into other soaps, incense sticks, essential oils, hand washes, talcum powder etc.

Nonetheless, the Mysore Sandal Soap remains the company’s flagship product, the only soap in the world made from 100% pure sandalwood oil (along with other natural essential oils such as patchouli, vetiver, orange, geranium and palm rose). Due to tremendous brand recall and loyalty associated with the soap, it also bags a prized position on the shopping lists of visiting NRIs.

In 2006, the iconic was awarded a Geographical Indicator (GI) tag — that means anyone can make and market a sandalwood soap but only KSDL can rightfully claim it to be a ‘Mysore Sandalwood’ soap.

Thanks to this near-monopolistic presence in the market for sandalwood bathing soaps, KSDL has also become one of Karnataka’s few public sector enterprises that turns consistent profits. In fact, the company registered its highest gross sales turnover (of ₹476 crore) in 2015-16.

Such is the legacy of sandalwood and this earthy, oval-shaped soap in the state that even Karnataka’s thriving film industry calls itself Sandalwood!

Today, there are a multitude of branded soaps in the market but Mysore Sandal Soap continues to hold a distinctive place among all of them. Its production figures continue to rise, even as the availability of sandalwood is on the decline.

To counter this, KSDL has been running a ‘Grow More Sandalwood’ programme for farmers, that provides affordable sandalwood saplings along with a buy-back guarantee.Working in partnership with the forest department, it is also working to ensure that for every sandalwood removed for extraction, a sandalwood sapling is planted to replace it.

The story of Mysore Sandal Soap and its enduring appeal is an inspiration not just for Indian PSUs but for the entire FMCG sector. Here’s hoping that its future is aromatic as its history!

Source….www.the betterindia.com

Natarajan

THE NEWSPAPER ERROR THAT SPARKED THE NOBEL PRIZE

“The merchant of death is dead,” blasted a French newspaper in April 1888, bidding good riddance to Swedish inventor and arms manufacturer Alfred Nobel, who “became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before.” Pretty harsh words for an obituary, especially when its subject was still very much alive. But even if the rumors of his demise were greatly exaggerated, the inventor of dynamite was not about to let the details of his legacy be similarly blown out of proportion, and so Nobel set out to ensure that his name would forever be tied to humankind’s highest achievements, and not its destructive potential.

“Nobel was a torrent of ideas, a perpetual inventor,” writes Jay Nordlinger in Peace, They Say: A History of the Nobel Peace Prize. It was no accident. His father was an engineer and inventor who specialized in blowing things up, and whose undersea naval mines had been used by the Russians to keep the vaunted British navy from besieging St. Petersburg during the Crimean War of the 1850s. Born in 1833 in Stockholm, young Alfred never earned a degree or attended college, but in addition to absorbing his father’s explosive knowledge, he traveled widely, learned several languages and trained under a world-renowned chemist in Paris. At the age of 24 he obtained his first patent, the first of more than 350 he would earn in his lifetime.

Nobel’s biggest breakthroughs came when he successfully harnessed the destructive power of nitroglycerin, including in dynamite, his most famous invention, which facilitated canals, tunnels and other infrastructure projects. Nobel was also, says Nordlinger, a “genius businessman” and entrepreneur, who not only invented the products he sold but also directed their manufacturing and marketing. And he was a prolific writer and lifelong bachelor. “My only wish is to devote myself to my profession, to science,” he wrote in 1884. “I look upon all women — young and old — as disturbing invaders who steal my time.”

But the Swede’s single-minded devotion to his work paid off. He would eventually oversee more than 90 labs and factories operating in more than 20 countries around the world, and he spent most of his time traveling between them, prompting French writer Victor Hugo to label him “Europe’s wealthiest vagabond.” Nobel’s employees adored their vagabond chief, though, and his factories offered free medicine and medical care. In addition to his generosity, Nobel was known for his insatiability, once observing, “I have two advantages over competitors: Both moneymaking and praise leave me utterly unmoved.”

What moved him profoundly, however, was being pronounced dead and a merchant of death. The press had confused Alfred’s passing with that of his older brother Ludvig, who succumbed to tuberculosis in 1888. It was a regrettable mistake that nonetheless afforded Nobel the rare opportunity to read his own obituary. “It pained him so much he never forgot it,” says Kenne Fant in Alfred Nobel: A Biography, and the insatiable inventor “became so obsessed with his posthumous reputation” that he would not rest until he had crafted “a cause upon which no future obituary writer would be able to cast aspersions.”

Finally, on Nov. 27, 1895, the inspired inventor sat down at a desk in the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris and, in handwritten Swedish with no help from a lawyer, penned a four-page document that would become one of history’s most notable last will and testaments. In it, he left 31 million Swedish kroner (equivalent to about $250 million today), the bulk of his estate, to be invested and the interest from which given “in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.” Four random gentlemen at the club were asked to witness the document, which now resides in a vault at the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, and the rest is history.

When he died, for real, the following year, Nobel’s will shocked his disappointed relatives, as well as the Swedish royal family, upset that he would establish a valuable prize whose competition was open to everyone, not just Swedes. But the prolific inventor, resolute and innovative to the end, had gone out with a bang, and true to his wishes, the name Alfred Nobel, no longer linked to death and destruction, would forever be associated with progress, peace and the very best in human achievements.

Source…Input from a friend of mine

Natarajan

Natarajan